By Dale Forbus Hogle

Board Member Magnolia Historical Society

Then: Seattle’s Sewage Comes to Magnolia’s West Point –1911

It all began in 1884 with the arrival in Seattle of the visionary engineer, Reginald Heber Thomson. Thomson had noticed that Lake Union and Lake Washington were getting horribly polluted because residents were dumping raw sewage directly into their waters. As City Engineer, he began studies for a plan to move the sewage out of city lakes.

In the fall of 1904, Thomson hired Fred Dehley and directed him to study the currents that touched the waterfront anywhere between two miles south of Alki Point to three miles north of Shilshole Bay. Next, Dehley was to place floats near the shore and to keep records of the hour and place at which each one floated out to sea. From these studies, Dehley located a short stretch of beach in Fort Lawton where there was always an outflow to the north whether the tide was incoming or outgoing. This was the place Thomson was searching for.

The City began a complicated process for getting permissions for the location of Thomson’s proposed sewer line. Congressman Humphrey secured an Act of Congress, dated the 10th of April, 1909, authorizing the right of way to run the sewer line through Fort Lawton and the Lake Washington Ship Canal. The City of Seattle passed Ordinance No. 20991 recognizing and accepting the Act of Congress. Finally Thomson’s plan could be realized.

Based on Dehley’s studies, West Point’s north beach in the northwest corner of Fort Lawton was the site selected for the outflow of Seattle’s sewage. Previous dumping into Lake Union and Lake Washington was abandoned, and in 1911 the new sewer line outfall discharged at a depth of 45 feet below high tide into Puget Sound. In 1918, the larger 12-foot diameter North Trunk Sewer was completed. It ran under Fort Lawton through a tunnel and again discharged its burden into Puget Sound at West Point. But even fast moving currents did not prevent the brownish plume occasionally depositing slime on the beach.

—

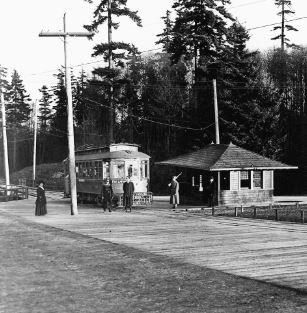

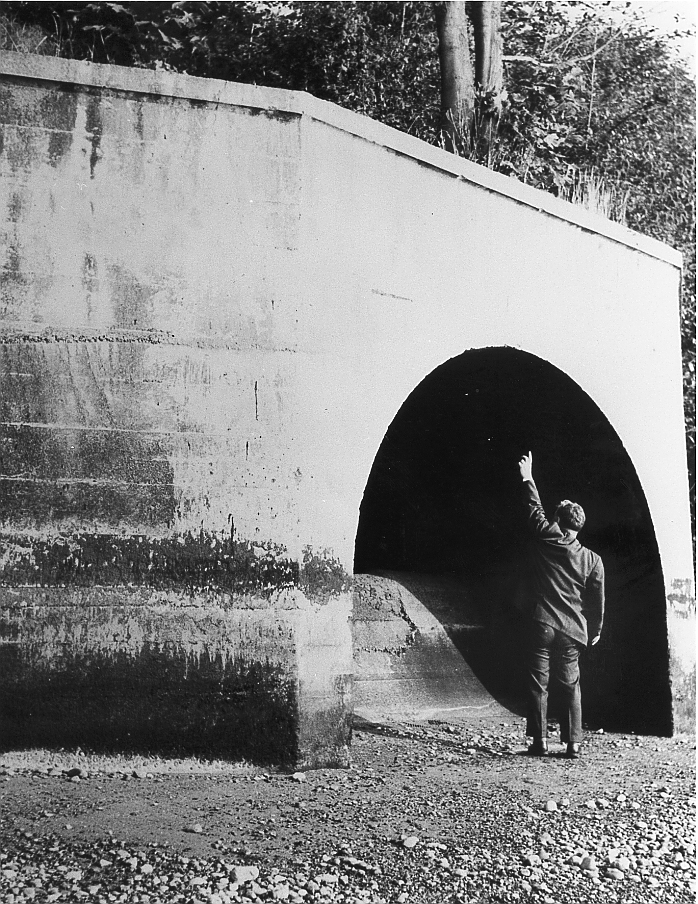

West Point terminus of the twelve-foot-diameter Fort Lawton tunnel

constructed in 1911. Weir just inside the portal

diverted storm water and sewage directly onto North Beach.

King County Archives,

#W1-153. Circa 1963

Now: Wastewater Treatment Plants come to West Point

1966 – Primary Plant 1995 – Secondary Plant

In 1958 voters approved the establishment of Metro (Municipality of Metropolitan Seattle) with powers to address the problem of sewage still fouling the clear waters of Puget Sound… West Point was a natural location for the Primary Treatment Plant because the main sewer trunk was already in place. Right of way was not difficult to acquire since the Federal Government owned Fort Lawton and West Point. In 1966 the plant was completed, and all Metro had to do was simply redirect the raw sewage from the trunk line into their new treatment system.

—

Aerial photograph of West Point. Metro has filled

portions of the North Beach prior to construction

of the primary treatment plant. The raw sewage

plume from the original outfall reflects the increase

in population.

Metro King County Archives. Circa 1963.

In 1972, the Congress passed the Federal Clean Water Act requiring secondary treatment at all municipality wastewater plants. Metro began the action to improve the West Point plant as demanded by the Congressional Act. Other locations for the new plant were sought, but the costs found to be impractical. In 1988, the Seattle City Council voted to grant the shoreline permit.

In 1991, 80 years after the Thomson’s early efforts to rid Seattle of its sewage problems, and nearly 30 years after the building of the Primary Treatment Plant, Metro began construction of the Secondary Treatment Plant. By then, Fort Lawton had become Seattle’s Discovery Park. Strong opposition from the community and Park lovers arose, so compromises were reached, mitigation funds were promised, and certain beautification features were agreed upon. In 1995, Metro, now King County Department of Metropolitan Services, began Secondary treatment.

—

Secondary Plant Expansion: Aerial photo of West Point looking southeast

into Discovery Park, showing the landscaped berm and beach trail.

The USCG lighthouse residences and VTS radar tower are bottom left. Three

of the six digesters and two covered rectangular primary sedimentation

tanks are center. The other three digesters, offices and the biosolids-handling

buildings are right. The open round secondary settling tanks are upper

left. The treatment plant’s HPO basins are just off the photo, north of

the settling tanks.

King County (WPsmallaerial.JPG). Circa 1999.

Today, a century after R.H. Thomson dreamed of cleaning up Seattle’s beautiful waterways, his dream is fulfilled.